Nan

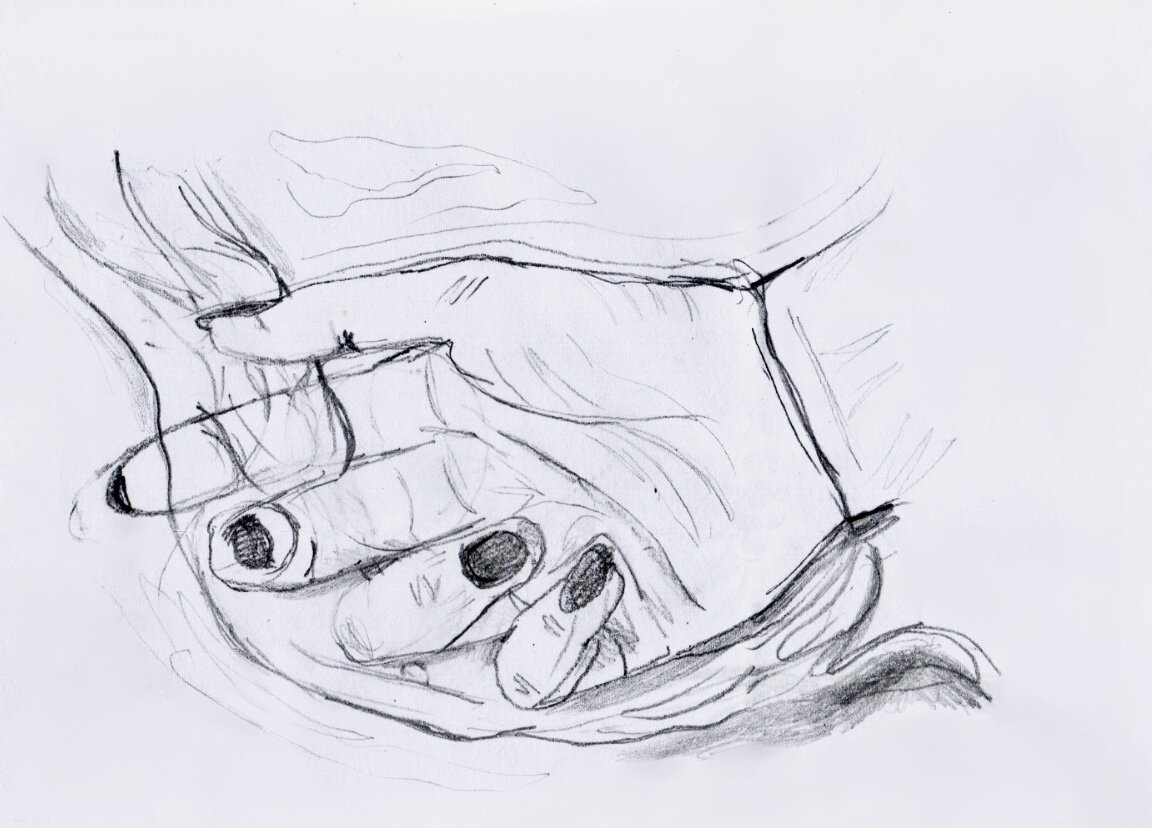

Illustrated by Maja Kobylak.The texture was soft, like crepe paper. No, not crepe paper– even that was too rough, too papery. It was more like silk. Worn silk, where you can see the shape of your fingers beneath the fabric, and it cannot win a fight against sunlight, much less anything else. There is a sort of beauty in such fragility, in the delicacy of such a fabric, when a texture is so soft that you feel like a sudden movement may break it.

It would have been beautiful if it was not my nan’s hand that I was holding. If I could marvel at the softness of the texture but then put it away, and not worry that I would break her. She looked so frail lying in the bed, one hand on her chest, rising and falling with her breath. Even that sounded weak, despite the clear arduous nature of the movement, and I had to strain to hear her breath, to see movements beneath the thin membrane of her eyelids. It was hard to remember a time when she wasn’t like this, but there were vague memories of time spent with a woman who looked like this one, but who had so much more vibrancy and life and colour.

My nan always seemed to have too much personality to be stuck inside such a small body. She hated it, hated that all her great-grandchildren were taller than her by the age of ten. I always found it remarkable that such a small frame could hold so much within. She had a nice personality, of course. Nicer than the children I went to school with, and the adults my parents worked with, even nicer than her daughter, who had a tendency to speak without thinking. Maybe it was that nan was always careful with words. Or maybe she wasn’t, and all of her words were simply pleasant.

‘Nice’. It is such a weak word to describe my nan. The woman who used to let two wriggly children ride on her scooter at a time, running off with us down the street at a speed that was far too fast to be remotely safe. My sister and I would shriek, and even as pedestrians had to leap out the way, they smiled.

We used to go to the beach with her. Not for long– even then, she could never spend too much time away from home– but long enough for memories. For small snapshots of her figures coming towards us, invariably on that small red scooter. Images of her holding ice-creams, and explaining to us why strawberry sauce was called monkey’s blood.

I remember we used to count pennies, little coppery things that always felt so cold, and she would pass them to me, her fingertips cool and dry. Her hands were soft then, too, but she always told me that it was hand cream that made them that way. I had been vaguely terrified at the idea that the cream in her bathroom could turn my hands as wrinkly as hers, and had avoided such cream for quite a few years thereafter.

She probably would have enjoyed that, but I don’t think she ever knew. She had a rare sense of humour, the kind that people call evil without meaning it, a vivaciousness that was a few steps away from outright maliciousness. The kind that laughed when people fell, when they dropped things, when they stumbled over their words, a kind that thrived on impersonations and impressions. It suited my nan, and I still believe that it wouldn’t have fitted anyone else so well.

There was a garden next to her flat. Not her last flat, with the high windows and the cream walls, but the first one. The one she lived in when I was born and where she held me. There are photos littering the walls of so many houses, four generations together and smiling. The dark walls, the small window, the kitchen with a strangely green tint that always perplexed me. She loved that flat, such that she never wanted to leave. My favourite thing about it was the window, the way you could look out and see a small birdhouse and so many flowers. My memories have made them lush and huge, in shades of pink and purple and cream, peach and blue, green and white and yellow. It had always seemed magical, like the kind one read in fairy stories, where insects and bugs lazily flew. It was shared by twenty or so flats, and I only went there once, but it’s one of my most vivid memories. Running around, shrieking, smiling, Not just me, but everyone– parents, grandparents. My nan.

There must be more memories. I know there are, I can feel them, a kind of warmth in my mind. A glimpse of a smile, something that makes me smile even though I don’t know why. Pennies and icecreams and beaches.

There must be more. I hate the idea of there not being more, of so many memories being wiped away and eclipsed by years of illness and whispering. Of false memories and nurses and the need for more care, always more nurses and drugs and doctors. Of hearing about the morphine, and that she’d been on it for years because none of her bones had worked since she’d been sixty. My nan was eighty when I was born, but by the time I was ten she was on the same dosage you would give a horse. And she was so, so small. Too little for all that, but she did it.

Of course she did. And she never complained. Even towards the end of her time in that flat with the garden, when she was starting to forget, she did it with a smile. Even when things got really bad, and she moved to the apartment with the tall windows and the cream walls, and she didn’t know who you were, she was still glad to see you. That was when I started to see the nurses rather than the carers, happy and smiling and oh–so–vexing to my nan, who hated them on the principle that she needed them. She was so pleasant with us, kind and sweet and giving. Yet when the carer entered, she morphed into someone I didn’t recognise, and then she was glaring and spitting and shouting. But then the nurse left, and everything went right back to how it was, and she was smiling and offering tea, chocolate, and biscuits. It was how I knew things were getting bad, when she stopped offering and just started sitting, staring, falling asleep in the middle of conversations. I didn’t mind. No one did. We all just thought she was tired, not sleeping well or having trouble with the pain. It was everywhere by that point. Her back, her knees, her hands. Inside her head.

I was still shocked when we got the call. Not the one about her being in hospital, for that happened too often. It was still worrying, of course, not knowing how it would affect her, how long she would be in hospital, how we were going to get her home. But she had always been alright in the end, back in the home within a week, hating all of the carers and loving all of us. I had no reason to believe that this time would be any different. I didn’t notice the tightness around my father’s mouth and the worry in my mother’s eyes.

I should have realised when they let me and my sister visit her in hospital. Our parents had never allowed this before– they thought it would be too unsettling. Not that I would understand, of course. I would always ask to go, always be denied. The child that I was, I thought that I had finally won the argument, earned the privilege. I felt oddly proud of myself on the journey there, so smug and conceited.

I had never been in a hospital before, never beyond the waiting room at least. She was in a room with four other women, all white–haired and lying down, with tubes in their nose and eyes that didn’t focus. And that was when I knew that something was wrong.

My nan was happy to see me. I could see how much she needed a smile, a nice word, some positivity. But I couldn’t give her that. I couldn’t get closer, I couldn’t say the right thing, I couldn’t do anything other than sit and watch. Eventually, everyone else was talking to doctors or nurses or just had to leave, and it was just me and my sister left. My nan was asleep, or her eyes were closed at least. We could have gone, but I didn’t want to leave, and neither did my sister. I was scared that if we left, she would wake and she would be alone. So we stayed, and eventually we each had a hand.

It was then that I noticed the texture.

She was so delicate. Not as a person, of course, because I had always known that she was strong and fierce and tenacious. How could a woman who had driven ambulances during the war be anything but strong? How could someone who had survived twenty-two years as a widow be anything but fierce? How could someone so funny and charismatic be anything but tenacious?

But her body was delicate, and soft, as though I could blow her away if I breathed too hard, if my crying got any louder than hushed sobs. I held my breath. She slept through us leaving. My goodbye was simply a light squeeze of the hand, so brief that she probably thought she had dreamt it.

It was the last time I ever saw her.

Silk is a nice texture. I just wish my nan had been made of something stronger.