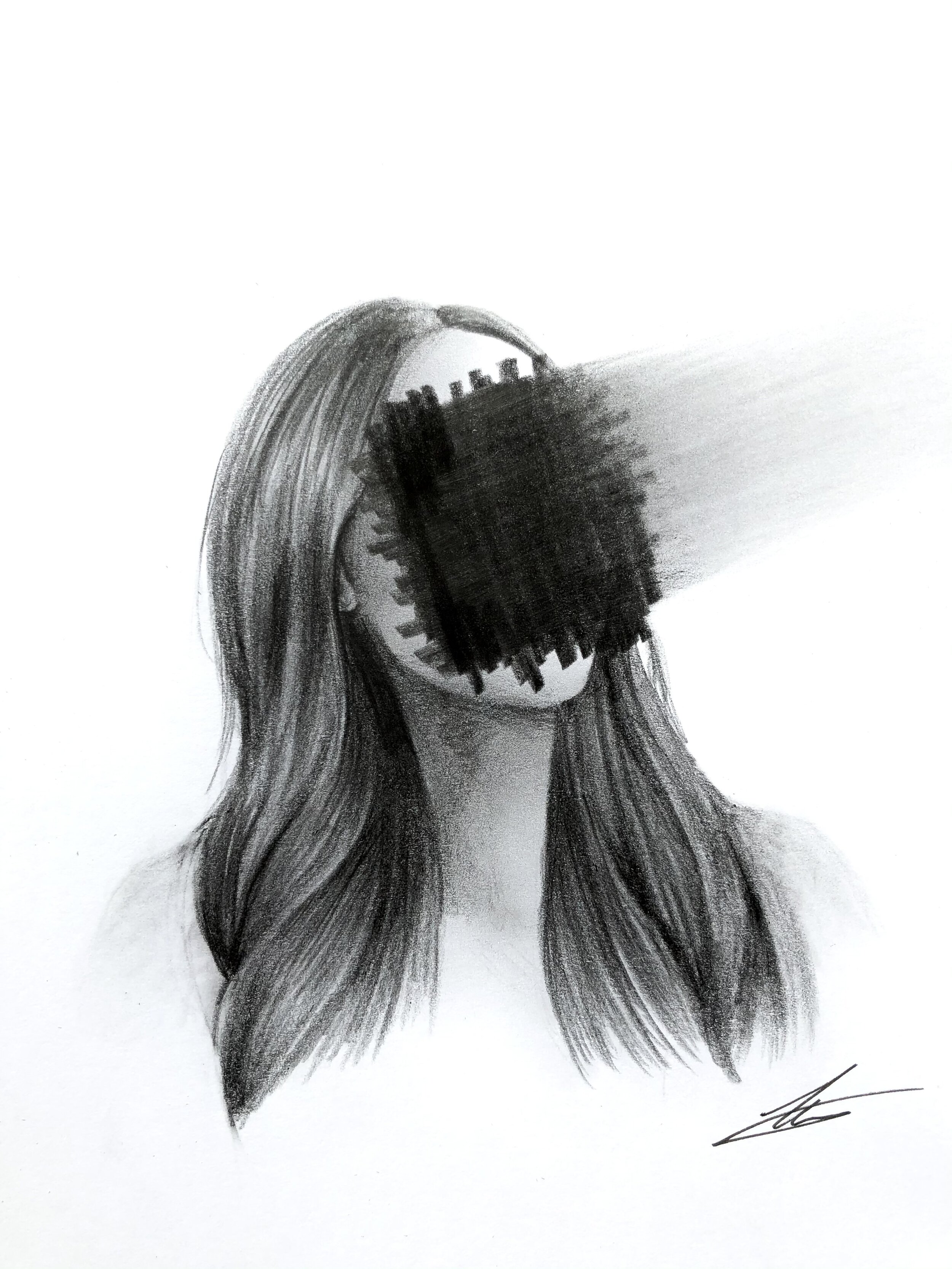

The Waiting Staff

Illustrated by Tula Wild.It had to be a set-up.

Agreed, the swollen eyes had not been on the uniform list, but you were wearing the rest of it: the white shirt; the grey trousers with belt loops; the black trainers.

Are you sure you’re allowed to wear those? your mum had asked. They’ve got a red strip along the edge?

No one’s going to be looking at my feet.

Or my face, you could have added. They might glance at the hands as you cleared their rubbish. And the chest could be useful at times. But the face wasn’t important. Except the men in the kiosk seemed to have noticed your red eyes, as they’d been laughing ever since you reached the front of the queue.

‘Cocktail stand,’ the one on the left repeated, and the man beside him wrote something on a clipboard.

‘But – I thought I was just here to clean?’

‘We’ve had a reshuffle. You’re needed out front.’

As you changed into the black shirt and tie you still maintained that this was a good idea. Not the toilet-cry – that had been misjudged – but the rest of it. And anyway, how were you to know that the clock-in time for agency staff was eleven-fifteen rather than eleven-thirty? You could have blamed it on allergies when you reached the desk, then perhaps the men wouldn’t have teased you so. But a weeping cleaner, you thought, while not ideal was neither disastrous. A weeping bar-maid was less appealing.

You looked at yourself in the porta-loo mirror. The shirt was too big, and they’d given you a staff badge, but it had been recycled from last year’s music festival and so under the Here to help it read Moira which wasn’t your name. It was a pretty name though, so you didn’t mind too much, and at least they’d matched the gender right this time.

You joined the crowd of people dressed identically to you as a man in a high-vis jacket led the way to each of the bars, depositing a few people at each one. You were the last to be assigned. He didn’t even take you there, just pointed to a gazebo on the far side of the London park where a woman was standing in a small pop-up bar barely two meters in width.

‘Are you mine?’ she asked when you reached her.

She had a face round and flat like a dinner-plate and a thick Polish accent.

‘I think so,’ you replied.

‘Ever made cocktails before?’ she asked.

‘Not really.’

She sighed something under her breath that didn’t sound like English.

‘You better get round here then,’ she said and handed you an apron.

As you fumbled with the strings she cleared a spot for you to stand and showed you around the pop-up bar with the carefulness of a patient lover.

‘Here is the fridge where we keep the bubbles. Here is for champagne. Here is for prosecco. Here is where we keep the glasses. Here is where we polish them. Here is where we keep the clean ones and here is for the dirty ones. Here is where you chop.’

And here is where you place your hand to make me love you.

When she’d finished she looked you up and down slowly. ‘Hangover?’ she asked.

‘Heartache.’

‘Shit. I have nothing for that.’

You both looked around at the stacked boxes of spirits that were clustered around your feet.

‘Help yourself,’ she shrugged. ‘But I will have to send you home. Maybe that’s what you want?’

You shook your head. ‘I want to be here.’

She nodded. ‘Then you better get unboxing.’

The public would start being let into the arena at one pm. The VIPs would come in first – they were the ones with the red ticket – and then everyone else would follow. The cocktail bar was on the furthest side, just tucked round the side of the stage, so it would be a little while before any customers reached it.

You had both finished setting up, and while she measured coins into the metal till you polished glasses over and over in the way she had shown you.

‘Is that your real name?’ she asked, gesturing to your badge as she counted 10p coins into her hand.

‘No.’ You placed the glass down and looked at her badge, which said Agatha. ‘Is that yours?’ you asked.

She glanced down at it. ‘No,’ she said. She smiled. ‘But I quite like it. You can stop cleaning those now,’ she added as you moved to pick up another glass.

She finished setting up the till, shutting the metal draw with a clang. She turned and squinted at you for a moment. ‘Can I ask – why are you here?’

You felt yourself go red.

‘I don’t mean like that,’ she added with a quick gesture of the hand. ‘Just – are you trying to punish yourself?’

‘I thought it would do me good. Keep my mind occupied.’

‘You knew it was coming then – the heartache?’

You shrugged. ‘Sort of. I knew it would have to end.’

‘Planned heartache.’ She shook her head. ‘The worst kind because there is not even someone to blame.’

It was a bright day, warm but not stifling. The dusty grass of Hyde park was beginning to become spotted by groups of people with blankets and camping chairs, all dressed for a day out and smiling to one another, but angled always towards the large stage that had been set up at the front. It was almost ready for the first act, not that you could tell from where you both were stationed, but occasionally figures dressed in black with wiry headsets would race across the green, and you could hear instruments being tuned.

At the cocktail station there was a constant trickle of customers, most asking to borrow a plastic cup or enquiring about prices. You’d both set up some tables nearby, around which people had gathered, fragments of conversation drifting to the bar so the two of you could stand side by side catching at them.

‘Do they look at us do you think?’ you asked eventually.

‘Do you look?’ she replied. ‘When you’re on the other side.’

You thought for a moment. ‘I think I try. Now that I’ve been in the position.’ You nodded at the group of men in shirts that stood at the nearest table. ‘I can’t imagine those lot have ever stood here.’

‘You can’t possibly say. You would only be guessing.’

‘But look at them. They’ve got VIP lanyards.’

She shrugged. ‘You can’t possibly say,’ she repeated.

There was a pause. You both watched as one of the men gesticulated wildly while the others looked on. It was hard to tell exactly what he was talking about. Perhaps a sports game or a fight, or retelling a particularly thrilling car-chase from a film. Whatever it was the others seemed interested and when he dropped his hands again they laughed loudly in unison.

You glanced up at the woman. ‘Is it men you like then?’ you asked.

‘Typically,’ she said. ‘And for you?’

‘Not so much.’ You nodded at the gathered group. ‘Who do you like of them?’

‘What makes you think I do?’

‘You seem curious.’

‘Curiosity is different. There can be attraction without reason.’

‘And attraction isn’t liking?’

‘Not always. Sometimes it is just about needing to know more.’

As the afternoon’s performances began the cocktail station drew a crowd. It was a while before the next lull in customers but meanwhile you both worked in efficient silence. She would hand you the glass before you’d asked for it. You would type in the order as she made it. When the last customer cleared she handed you a bottle of water and you suddenly realised your mouth was dry.

While neither of you could see the stage, you could hear the music and guess the spectacle from the reactions of the nearest people. You both stood side by side and watched the faces turned slightly away from you.

‘Do you enjoy this?’ you asked after a minute.

She didn’t reply for a while and you wondered if she disapproved of the question. Finally, she sighed. ‘There’s a power in handing over alcohol with a sober hand,’ she said.

You smiled. ‘I think I’d rather be on the receiving end.’

She looked at you closely again in that way that made you nervous. ‘How old are you?’ she asked.

‘Twenty. Why?’

‘Twenty and you are closed-off like your life is already over. I would have guessed much older.’

You laughed at this, more in outrage than anything else. ‘Closed-off? In what way?’

She gestured wildly. ‘That man there came just now, and you didn’t even speak to him.’

‘I did. I served him.’

‘You served him, yes. But you didn’t talk. There was no conversation.’

‘What could I have said? I was doing my job.’

‘Now it is my turn to laugh.’ She did, loudly and arrestingly. ‘That is a poor excuse. This is not what twenty is for.’

‘What is twenty for?’

She paused and shook her head. ‘Don’t think too much on big moments,’ she said. ‘There’s time for that when you’re older. Now is not for those. The excitement of being young lies in the little edges closer.’

You smiled. ‘What? You mean to people like him?’

She shrugged. ‘Maybe,’ she said, turning her back to you to chop mint. ‘Now you will never know.’

You watched the movement of her shoulders. You were not sure if you liked this woman or not, but she spoke things with a confidence that you found comforting, even if their content was beyond belief.

‘Is that what you do then?’ you asked after a silence. ‘Ask questions and hope for a good answer?’

‘Not a good answer,’ she replied without turning round. ‘Just a true one.’

‘Something to leave you thinking?’

‘Perhaps.’

She turned back towards you, picking mint leaves from between her fingers.

You handed her a cloth. ‘And what then?’ you asked. ‘They disappear into the crowd and that’s that?’

‘Exactly.’

You made a face.

‘You’re not convinced?’ she asked.

‘Why seek these moments out when you know they’ll be so fleeting?’

‘I see,’ she said, nodding. ‘You are the kind to stay until things come to you.’

‘Is that how I seem?’

‘You’ve got that look like you’re waiting for someone to find you. Lost dog. Like those ones tied up outside supermarkets.’

‘No,’ you said. ‘I’m not waiting for anyone.’

‘Just hoping then?’

She looked at you, but you didn’t reply.

The orchestra on stage had finished their set; you could both tell by the noise of the crowd. In the gap before the next musician people would notice they needed a refill. It would not be long before the bar was busy again with figures looking and reaching and asking questions while you both juggled them between you. Then as quick as they launched into an exchange they would quickly fall away.

You could see the crowd stirring. Shapes beginning to stand and crane their necks towards the little tents placed neatly around the arena. Meanwhile, together you both stood in anticipation of their arrival, and of starting something with each passing figure that never really felt finished.

But it was all beginnings for you now: first impressions and first exchanges; strangers and strange bodies and wanting someone to believe in. And how could you go from that when you were so used to knowing? And being known. There had been moments of doubt with her of course, but you had known the important things. You had known that she didn’t trust black cats and sell-by-dates, or declarations of love made in the dark. You had also known that your hold had always been in the reach of a hand in the morning, while her love was in those types of song where you’ve got to listen with closed eyes to really hear it. Together you had been the quiet sort – you knew that too. Just like you knew that since she’d gone you held yourself together in the shower – alone – hands cupped in the right places.

In the bar the woman wiped the counter-top with a wet cloth, ringing it out into a plastic tub at her elbow. She reached for the box of clean glasses, handing one side to you so you could both line them up.

‘Can I ask you something?’ you asked as the two of you reached in.

She smiled in the smallest corner of her mouth. ‘Of course.’

‘Don’t you find it exhausting?’

She shrugged slightly ‘Sometimes these people stick,’ she said.

‘Like who?’

She thought for a moment. ‘There was a man who left his wife,’ she said. ‘His children wouldn’t speak to him. He still blamed them. He could not see himself clearly yet.’

You smiled. ‘That sounds like a lot of men.’

‘He was not special, but that was what made him so memorable.’ She shook her head. ‘You don’t understand. There was something frightening in the eyes.’

You asked what it was.

She thought again. ‘The kind of thing that must be looked for to be seen,’ she said. ‘But once it is noticed it is so sure. It is as much a part of them as their own face, but it could not be found straight away.’

‘And that makes you afraid for them?’

‘For them, yes. But also for everyone, and for what can be seen in us all.’

You wanted to ask more, but already someone was waiting to order and you didn’t get a chance.

It was not long after that that you were called away to your lunch-break. As you sat in the shadow of the delivery trucks you thought about what she had said: about knowing and what you knew and all that was left to be known. The music from the stage could still be heard, though only faintly, and occasionally a figure in a high-vis jacket would appear and vanish between tents. A man with a clipboard asked you what bar you were on, and when you told him he said the crowd was big now and that you better get back. But when you returned the woman you’d been working with had been moved to supervise another bar, and though you stayed until the end of the shift she didn’t come back again.

At the close of the festival you waited to hand in your name-badge. The men were still sat in the kiosk. The same ones. You wondered what they’d say to you when you reached the front of the queue.

Stopped crying now?

Yeah… Sorry about that.

Good. That’s what we hoped.

What do you mean?

Didn’t you work it out? It was our plan all along. Put you in the world headfirst and so all you can do is grab onto those people around you. The passers-by, those fleeting conversations. Just enough to pull yourself to the surface again. That’s all you needed. We could see that clear as day. Just something outstretched to pull you up again.

But when you reached the front of the queue they didn’t say anything. They didn’t even look at you. Just took the name badge and asked you for the uniform back. Someone was in the porta-loo, so you stripped down to your bra while the other waiting workers stared at your pale tummy. No one asked your name as you left, just crossed a number off a spreadsheet, and you walked between the cones of light spaced evenly amongst the shadow of Hyde Park, feeling invisible, unknowable, but full of possibility.